TL;DR: I built a system where LLM agents can play Pokémon Showdown battles. After running 18 battles across OpenAI and Anthropic models, I found that Anthropic models won more often, probably due to better tool-calling reliability, though my harness design could also be biasing results. The total cost for a small tournament was $18 in inference API costs.

The idea

About 9 months ago, I was reading Claude Plays Pokemon and remembered Pokemon Showdown, a game my brother and I used to play in high school. We'd spend hours building teams and battling each other, trying to climb the ladder. At one point, I used to open it up everyday and grind out the ladder to climb the ranks.

The thought hit me: what if I could build something where AI agents battle each other? It sounded fun and I was curious if different models would actually play differently.

I also liked the idea of games as benchmarks. Unlike static evals where you're chasing some fixed rubric, games force you to adapt to another intelligence that's also trying to win. As always, Andrej Karpathy tweeted about this:

So I decided to build it.

Why Pokemon battles work as an eval

A standard Pokémon battle is surprisingly complex from a game theory perspective:

- Two players, each with six Pokémon

- Turn-based, but both players choose moves simultaneously

- Non-deterministic (critical hits, move accuracy, etc.)

- Imperfect information (you don't know your opponent's exact stats or strategy)

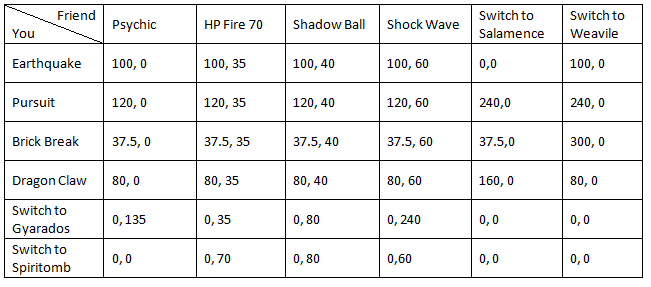

For a single turn, you can think of it as a payoff matrix:

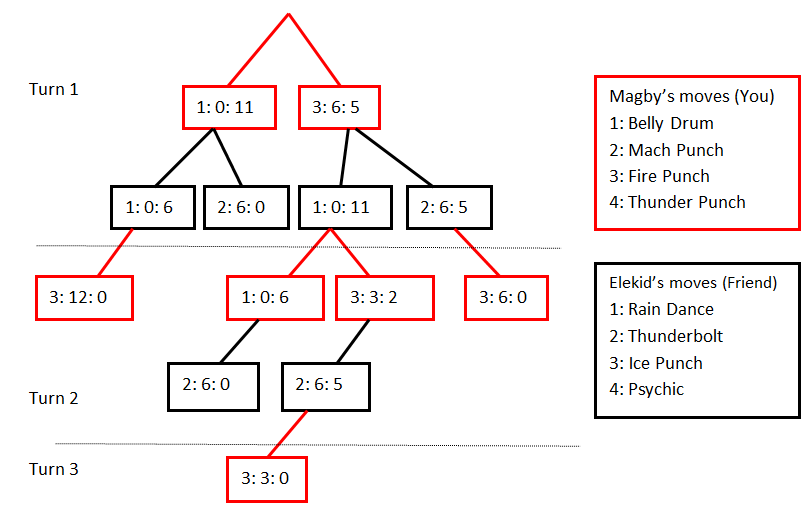

But over multiple turns, this becomes a full game tree:

I didn't go deep on formal game theory, but the basic insight is: choosing the right move requires understanding type matchups, predicting your opponent's strategy, and managing risk.

For example: your fire-type Pokemon is at 30% HP and facing an opponent whose type you don't know yet. Do you:

Switch out

Risking that your opponent predicts it and sets up a stat boost

Stay in and attack

Gambling that they don't have a water move ready

That felt like a good test for whether LLMs can actually reason about strategy and long-term planning.

First attempt (April 2025): letting Cursor do everything

Back in April, I got excited about the idea and decided to try building it from scratch using the modular Pokemon Showdown packages.

This was around the time when Dario was saying AI would write 90% of code soon, and I thought:

Sure, let's see if Cursor can just build this for me.

It couldn't. I spent days debugging websocket connection drops, multiplayer state management issues, and battle engine failures that models generated but that didn't actually work. I never got an agent to complete a single battle.

But I did learn a ton about websockets and multiplayer game architecture, so it wasn't a total loss.

Second attempt (October 2025): treating Showdown as a black box

After starting a new role and getting back to some semblance of normal life (short-lived, as it turned out), I came back to this project in October.

This time, I took a different approach: instead of building everything from scratch, I ran a local Pokemon Showdown server and treated it as an external dependency, just like the hosted version that players use.

Then, I used PokeEnv, a Python library that handles all the websocket communication with the Showdown server.

The only thing I had to do was implement a custom Player class that would:

- Convert the battle state into text the LLM could understand

- Let the LLM decide what to do (with tools if needed)

- Send the decision back to the server

This approach worked way better.

Formatting battle state

The Battle object from PokeEnv contains a lot of information: HP percentages, status conditions, available moves, type matchups, weather effects, and more.

I had to decide what to show the agent and what to hide. This ended up mattering more than I expected - the moment you choose a text format, you've basically decided what the agent "sees" as the game state.

I went with a structured text format that included the current active Pokemon (yours and opponent's), HP and status conditions, available moves and switches, and recent battle history (last N turns).

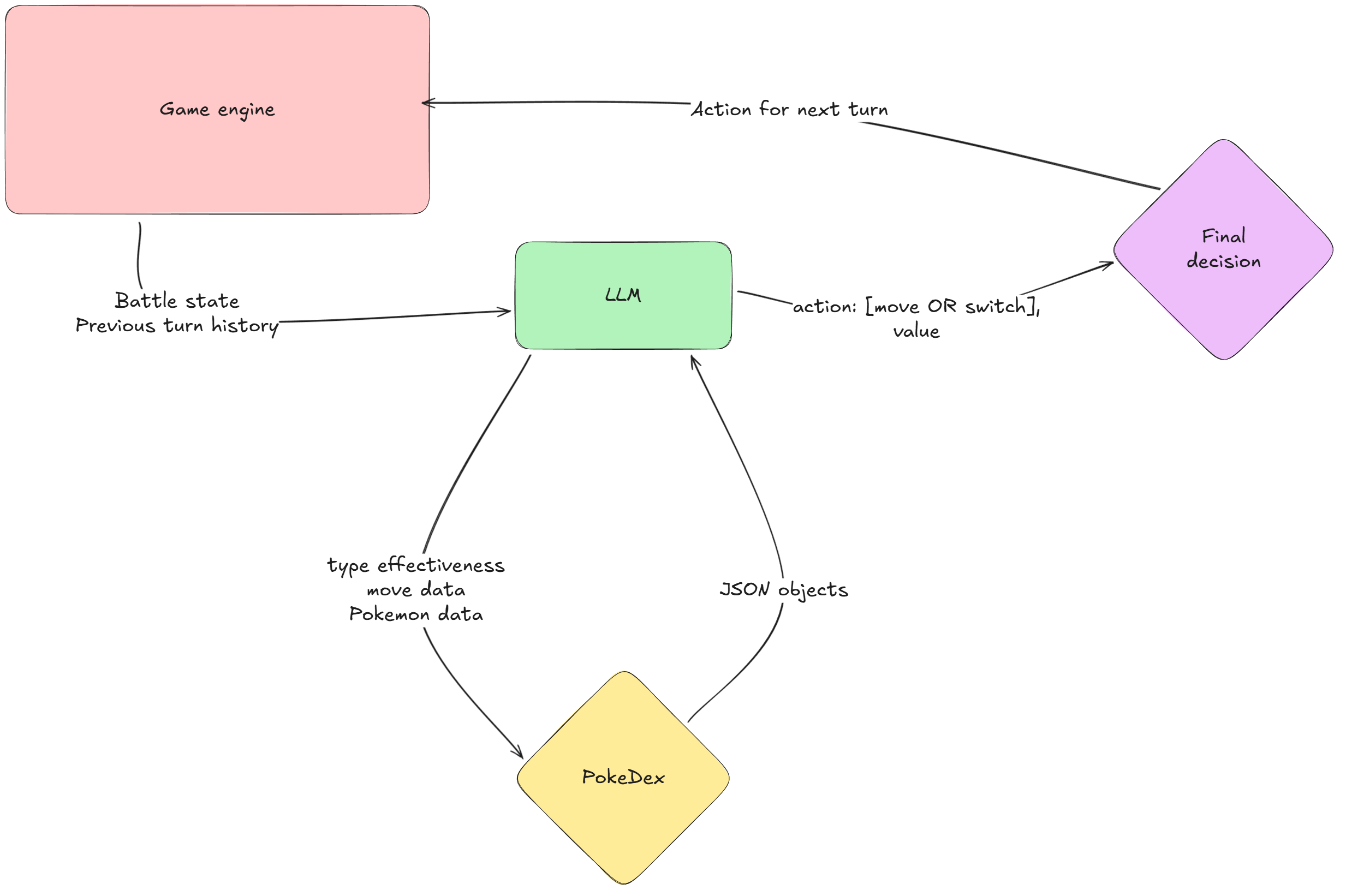

The agent loop

I built a simple tool-calling loop with the following steps:

- Agent receives formatted battle state

- Can optionally call a "PokeDex" tool to look up move details, Pokemon stats, or type effectiveness

- Must eventually call a "FinalizeDecision" tool with its chosen move

Initially, I had three separate tools (one for moves, one for Pokemon, one for type matchups), but I consolidated them into one tool that could do all three depending on the arguments. This reduced decision paralysis.

I used LangChain's new v1.0 SDK, which made it easy to add middleware for context trimming and logging:

self._agent = create_agent(

self._llm,

tools=self._tools,

system_prompt=self.system_prompt,

response_format=ToolStrategy(FinalizeDecisionTool),

checkpointer=self._checkpointer,

middleware=[

BattleLogsMiddleware(keep_last_n_turns=self.last_n_turns),

ToolMonitoringMiddleware(),

],

name=f"{player_username}",

context_schema=AgentContextSchema,

)

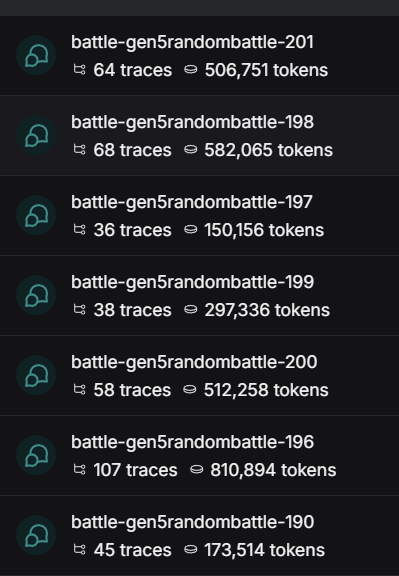

Everything also traces automatically to LangSmith, which made debugging way easier.

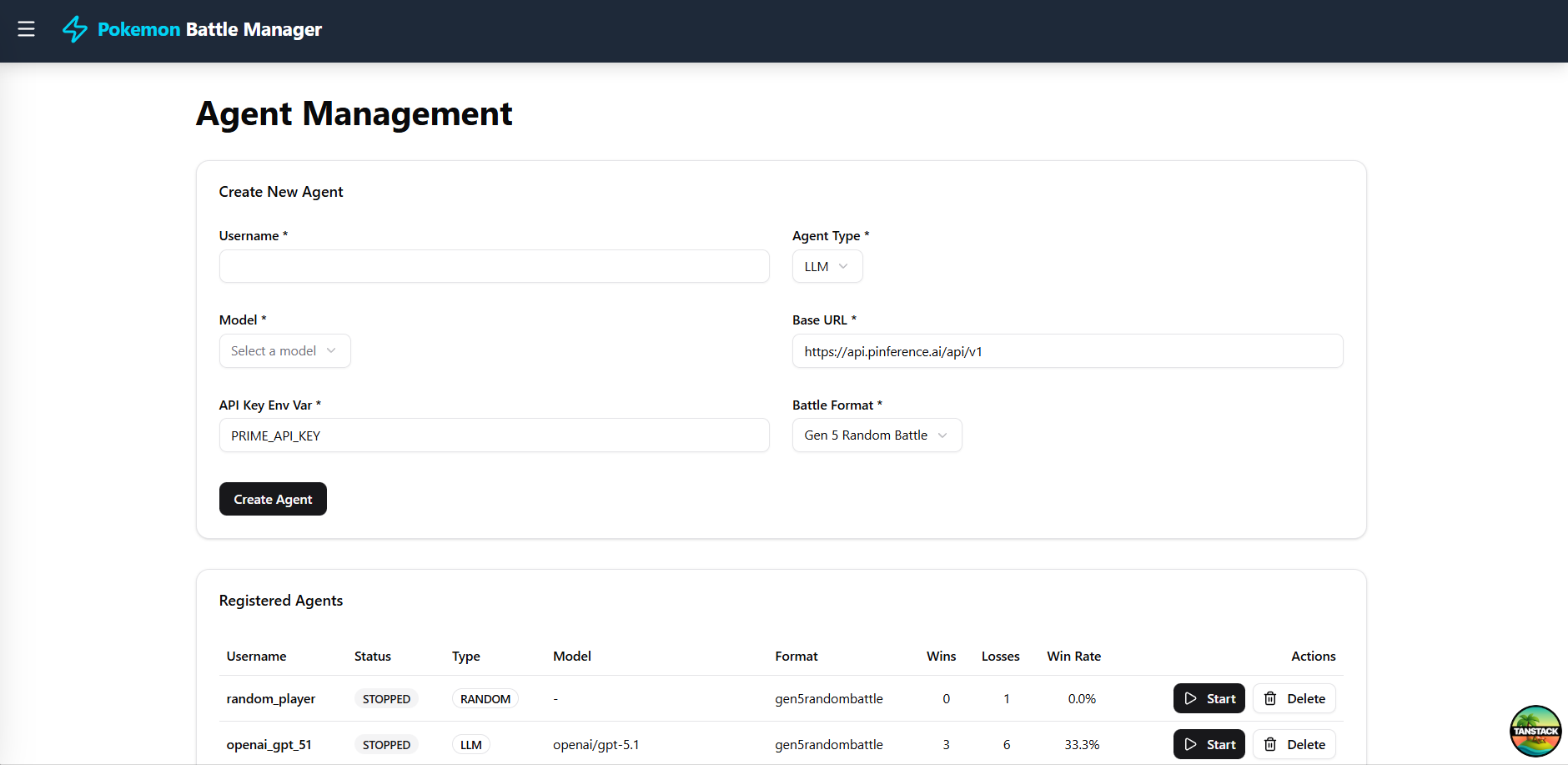

Building the admin panel

One of the unexpected fun parts of this project was building the admin UI. I started with a terminal app, then moved to vanilla JavaScript, then eventually to React. I used Claude Code for most of this: describing what I wanted, coming back to a working UI, testing it, and asking for fixes. I experimented with a battle viewer but re-parsing the logs to get the state got too confusing for the models.

Regardless, it was a nice little side-project within a project, and showcased the current capabilities of coding agents.

What changed between April and October

The gap between these two attempts was only 6 months, but it felt like years in terms of tooling maturity.

Models had gotten dramatically better at tool calling, codebase understanding, and maintaining context across long conversations. Coupled with standardizations in the ecosystem, things started to work reliably.

But the bigger shift for me was in realizing that Cursor (IDE) and Claude Code (CLI) aren't competing products, but rather different points on a flow state spectrum:

-

Cursor: Faster feedback loops and more suited for agent-assisted development. You're in the editor, iterating rapidly, making lots of small changes. The agent is like a really fast autocomplete (not Cursor Tab, that is different but so freakin' good!) that you can develop with.

-

Claude Code (and similar): Longer-running, more autonomous, and more suited for task-based development. You describe a feature or a bug fix, walk away, come back to a PR. The agent is more like a developer you've delegated a whole task to without providing a detailed plan.

For the second attempt, I used both approaches:

- Cursor for quick iterations on the agent harness, prompt tweaks, and debugging specific functions

- Claude Code for building the admin panel and handling larger refactors I didn't want to supervise line-by-line

The fact that both approaches now work reliably is the real story. In April, neither did.1

What I built

The system has four main pieces:

-

Local Showdown server: runs the actual game logic, just like the public version

Pokemon Showdown simulator interface -

Python bridge player: a custom

Playerclass usingpoke-envthat connects to the server

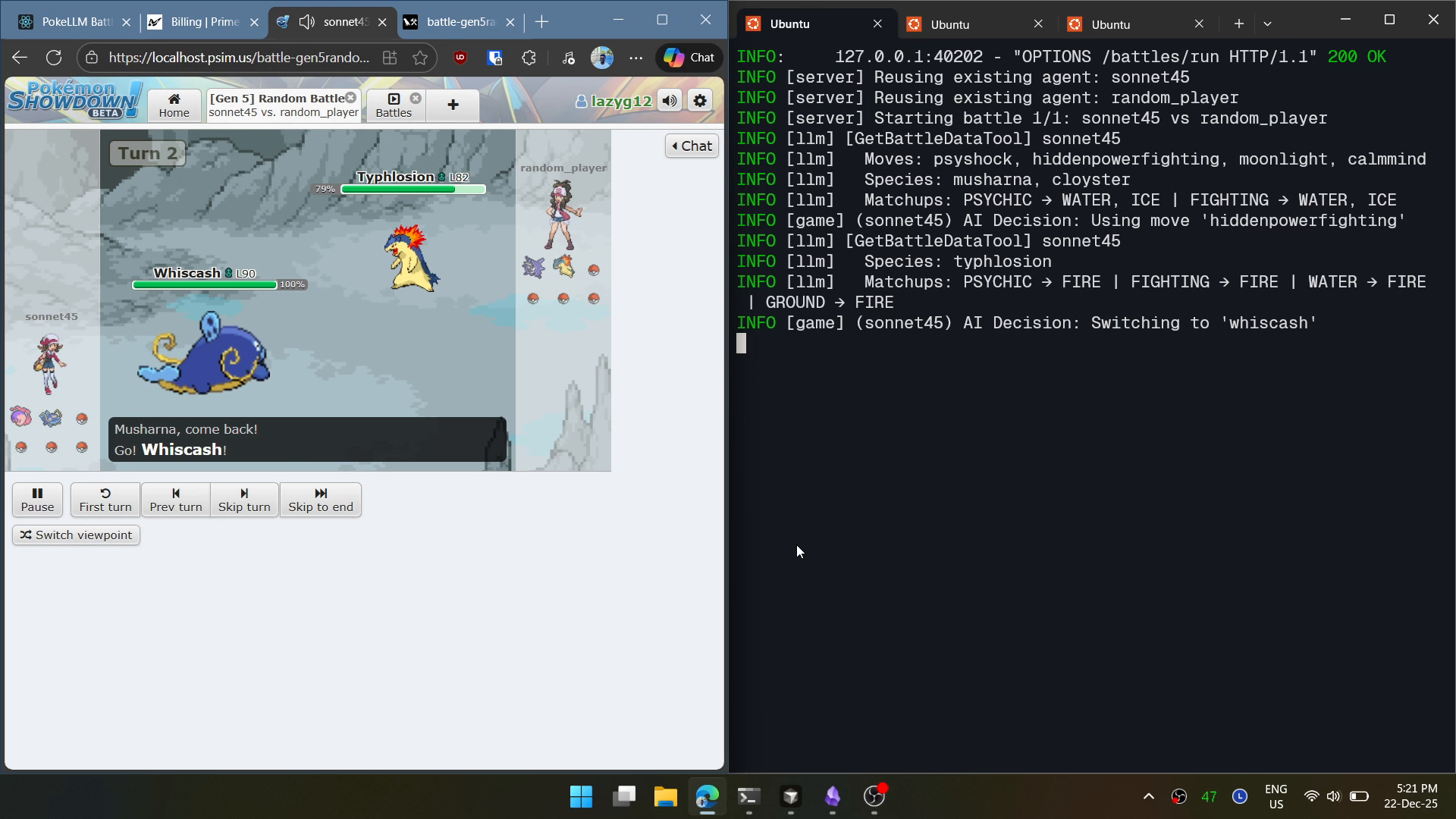

Agent logs in terminal -

LLM agent: a LangGraph-based agent that processes battle state → calls tools → returns a move

Agent design -

Admin panel: a small React UI to start battles, view history, and inspect logs

Agent management admin panel

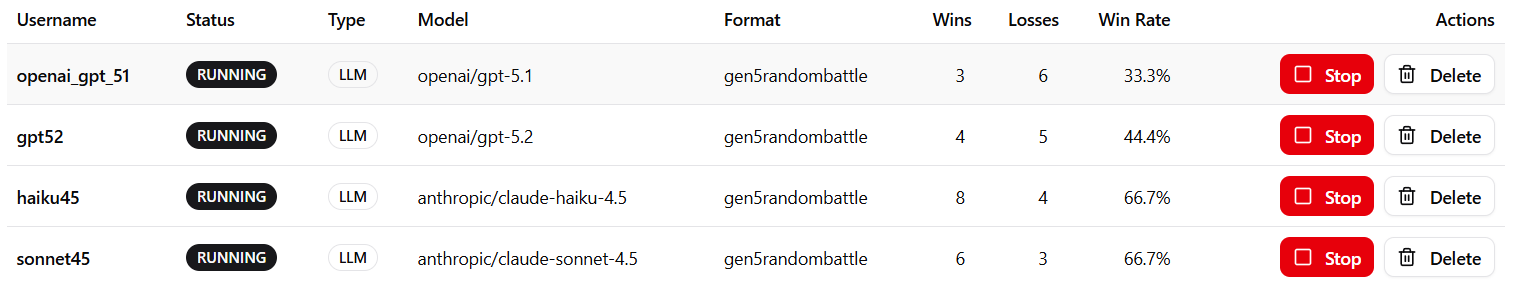

Running the tournament

Once everything was working end-to-end, I wanted to sanity-check that:

- Battles actually complete without crashing

- Different models behave differently

- The system could handle back-to-back battles

I ran a small round-robin tournament with 4 models, each playing 3 battles against every other model2:

openai/gpt-5.2openai/gpt-5.1anthropic/claude-haiku-4.5anthropic/claude-sonnet-4.5

Total: 18 battles.

Results

The Anthropic models won more often than the OpenAI models in this sample.

My working hypothesis is that tool-calling reliability is the main driver. The harness is tool-heavy: agents need to query the PokeDex and commit to a move via tool calls. If a model struggles with tool-calling, it loses time and gets into a context rot.

But there's a big confound: the harness design might favor a particular model's style. The exact prompt structure, how I format battle state, what context I trim, and which tools I expose could all be biasing results toward models that happen to align with those choices.

I haven't done a replay-by-replay analysis yet. This was more of a "does the system work?" checkpoint than a rigorous benchmark.

Cost and token usage breakdown

I spent a total of $18.10 on inference API served through Prime Intellect for the tournament.

If you're curious about what the agent reasoning looks like, here's a public LangSmith trace from one of the battles.

What seemed broken

Inspecting the logs, I noticed one clear failure mode: some models call tools way too often.

Instead of checking the PokeDex once or twice per turn, certain models would query it 4-5 times, with sequential arguments even though the description allowed for multiple arguments. Alternatively, smaller models would continue querying across turns even though the context contained the answer. This led to increased context accumulation through repeated calls, which increased token usage, driving up latency and cost.

If I come back to this, I'd add tool budgets: limit how many times you can call the PokeDex per turn, and make the tool outputs more "decision-ready" so agents don't feel like they need to keep querying.

The different battle modes

I ended up building three modes to test different aspects of the system:

- Human vs Agent: Can I play against it without it feeling stupid?

- Random vs Agent: Does it beat a trivial baseline, or is the harness fundamentally broken?

- Agent vs Agent: Do different models actually play differently, or do they converge to similar strategies?

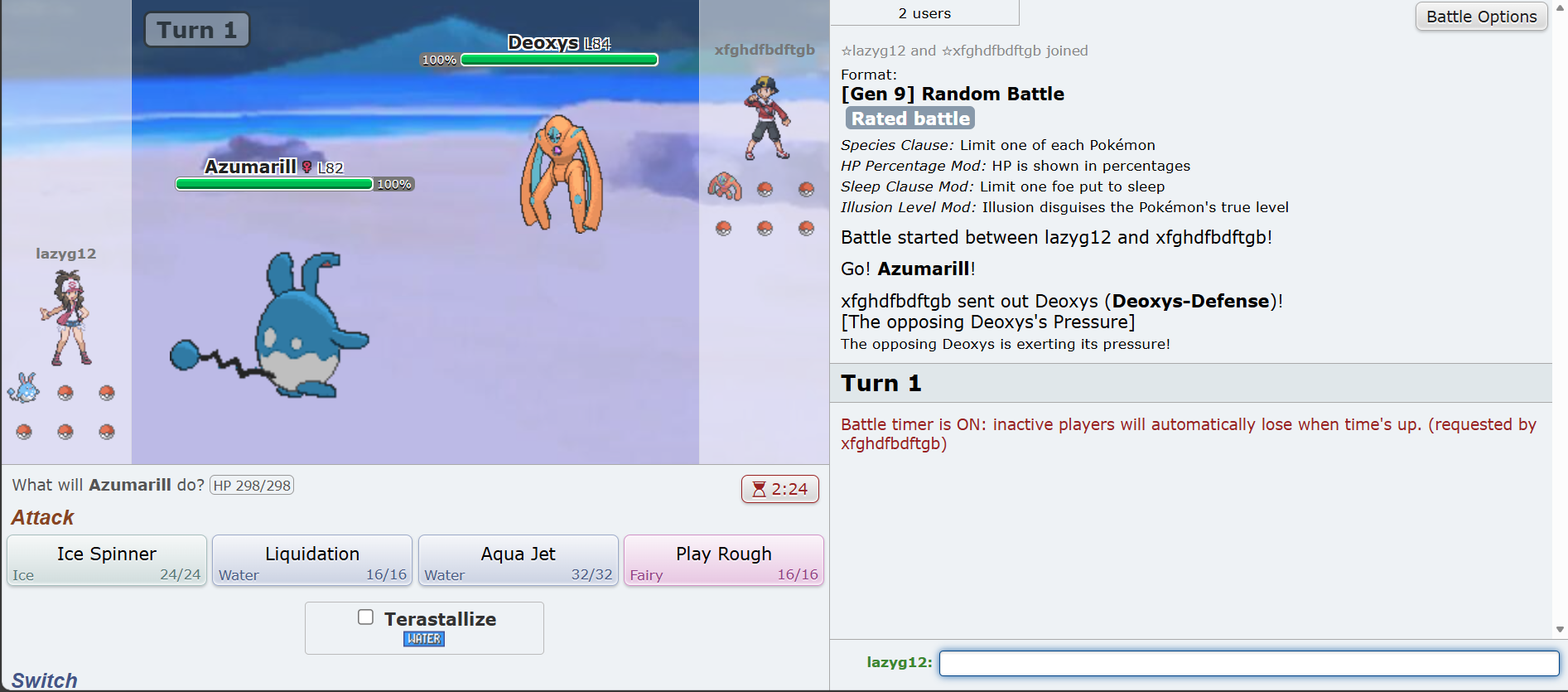

Human vs Agent - I can play against an AI through the Showdown interface:

Random Player vs Agent - A baseline comparison where the agent fights a bot that just picks random moves:

Agent vs Agent - Two LLMs battling each other:

What I'd do next (if I come back)

This project has been sitting in my head for 9 months. I've restarted it twice, demoed it to a few people, and kept tinkering with it on weekends. At some point, you just need to ship and move on.

But if I do come back to this, here's what I'd explore:

-

High-sample benchmark: Run hundreds of battles so the results stop being vibes and start being signal. Right now, 18 battles is enough to confirm the system works, but not enough to say anything definitive about model capabilities.

-

Better middleware with

deepagents: The LangChain team recently released deepagents, which has cleaner patterns for built-in tools, managing context, logging, and extensibility. I want to refactor my harness to use those patterns instead of my hacky middleware setup. -

Online learning / distillation: Ideas like On-Policy Distillation feel like a natural next step. If I can log thousands of self-play trajectories, maybe I could distill that into a smaller, faster model that learns to play Pokemon well.

-

Human vs AI platform: This is the most "product" direction this can go in - make it actually fun for people to battle against AI agents, track win rates, maybe even let people customize agent behavior. That feels like something that could be genuinely entertaining rather than just a technical curiosity.

Acknowledgements

This project wouldn't have been possible without the excellent work and research done by others in the Pokemon community:

- Pokemon Showdown: The incredible open-source battle simulator by Smogon that made this whole project feasible

- PokeEnv: Haris Sahovic's Python interface for Pokemon Showdown, which handled the websocket communication and battle state management with the server

- Game theory foundations: The articles on payoff matrices and game trees from Bulbanews helped frame the strategic complexity of Pokemon battles

- Academic research: Several papers informed my understanding of Pokemon as a strategic game:

Closing thoughts

I've been carrying this project around for months, restarting it, rethinking it, and never quite finishing it. At some point, I realized I was just avoiding publishing because I wanted it to be "more complete." But the truth is: it works, it's interesting, and I learned a lot building it. That's enough.

If you're working on something similar - or if you just think this is cool - I'd love to hear from you. Hit me up on X/Twitter or LinkedIn.

Footnotes

-

Between April and December 2025, both models and tooling matured dramatically. Tool calling went from unreliable to robust, and the coding agent ecosystem exploded across multiple surfaces: traditional IDEs like Cursor and Windsurf, terminal interfaces like Claude Code, OpenCode, and AmpCode, desktop apps like Conductor, and web platforms like Devin. Dario's prediction about "AI writing 90% of code" suddenly feels less far-fetched. ↩

-

I couldn't test

google/gemini-3due to a provider issue, unfortunately. ↩